Abbotsford’s Bold Abbotsforward Community Plan

This article, Abbotsford rethinks its future, by Jeff Lee was originally published by The Vancouver Sun on April 14, 2016. The original article also includes a video of Abbotsford Mayor, Henry Braun.

Abbotsford, where the vehicle is king and surface parking lots eat up more real estate than the strip malls they service, is about to undergo a revolution.

Sprawling, lacking a downtown core and yet hemmed in by the very agricultural economy that has made it what it is, B.C.’s largest city by land mass is rethinking its future.

If all goes according to plan, the next 60,000 people to move there will shape Abbotsford — population 140,000 — into a denser urban environment where residential and commercial towers replace car parks and the city grows up, not out.

This week, the city will finish public consultations on a new draft official community plan that contemplates turning South Fraser Way into a new city centre with a mixture of taller towers. If Mayor Henry Braun and his council have their way, the kilometre-long stretches between crosswalks in some places will be replaced by leafy, pedestrian-friendly boulevards broken up with people-friendly gathering places.

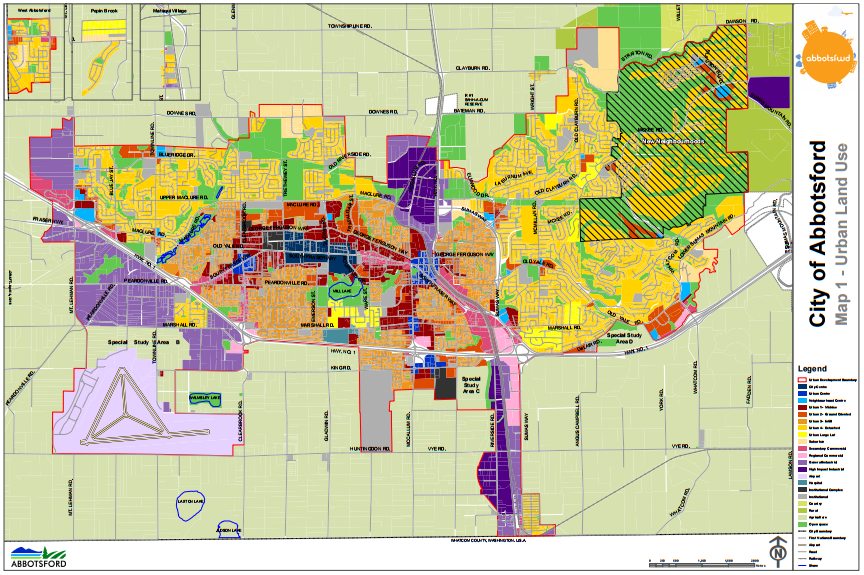

Traditional large-lot neighbourhoods could find themselves redefined with infill housing, including a relatively new form that’s popular in Vancouver: the laneway house. No new significant residential development will be considered outside an established “urban development boundary.”

It is an ambitious plan, and unlike traditional official community plans that build out over 20 or 25 years, it is based on outcome rather than a timeline.

“It certainly is a significant game-changer for Abbotsford,” said Brent Toderian, the former Vancouver planning director who is now working with Abbotsford on the draft plan.

“Instead of planning for a time frame, which is the usual way to do a plan, we planned for an outcome of 200,000 people. The conversations can be about that outcome. It doesn’t care if it reaches that outcome in 10, 20 or 50 years.”

It has been hard for Abbotsford to define itself. It is the fifth-largest city in B.C. by population. It has the second-largest airport in the Lower Mainland, a growing aerospace industry and enough traffic to put it among the top 20 airports in Canada.

It is the regional hub for the Fraser Valley’s vibrant farming community, where fields of blueberries and raspberries jostle with chicken and turkey farms and cow dairies and hay fields. With 75 percent of the municipality’s land base locked away within the protection of the Agricultural Land Reserve, that isn’t likely to change, either.

It is home to three of the largest prisons in the province. Between the agricultural zones and the urban development boundary are low-scale industrial zones.

Fully 65 percent of residents work in Abbotsford, according to Braun. The rest travel to Mission, Langley, Chilliwack, Surrey and, to a small degree, Vancouver. It is also a culturally diverse community. More than 23 percent are South Asian, making up 53 percent of the city’s total immigrant population. It has one of the oldest South Asian communities in the province, largely based around farming.

Yet for all that, Abbotsford has grown into a city by default. By 1995, when Matsqui joined Abbotsford — which had amalgamated with the District of Sumas in 1972 — planners had already defined the three municipalities. What is left of Abbotsford’s historic downtown is a fair distance from where the city has now emerged, further up South Fraser Way.

“We have a historic downtown, but if you ask six people where the city centre is, you will get four different answers,” Braun said.

A Fraser Valley sister to Surrey’s once-dumpy commercial-industrial King George Highway, South Fraser is, by Braun’s description, wide enough to be a runway and just as ugly. But it holds promise as a new identity for the city.

“Out of this will come a city centre that is inviting for people, where walking, cycling and transit will be delightful. It currently isn’t delightful,” Braun said.

Toderian is more direct.

“When you think of South Fraser Way now, it is your standard large-scale traffic sewer. It is surrounded by seas of parking and suburban shopping malls,” he said.

“We challenged the community and council hard to be bold about deciding whether the plan is a consolidation, a tweak or a rethink. To the community and council’s credit, I think they ended up being surprised by how much they wanted to rethink.”

The OCP calls for four new “urban centres” around the old downtown, the University of the Fraser Valley and at the South Fraser Way intersections of McCallum and Clearbrook. Of the 60,000 new residents anticipated, 45,000 will be in the urban core and surrounding neighbourhoods. The remaining 15,000 will be in new neighbourhoods developed within the urban boundaries.

The city is also setting aside four study areas where new industrial zones could be created from land within the Agricultural Land Reserve. But the Agricultural Land Commission, which governs such changes, has already signalled its reluctance to invade the valuable but shrinking supply of farmland. In February it rejected a developer’s plan to convert 224 acres in Bradner to industrial land. Area residents who had objected to the application greeted the decision with cheers. The Bradner properties are one of the four study areas and Braun says the commission may change its position if the city sees this as a useful part of the official community plan.

“I don’t think there is more appetite for having more sprawl,” Braun said. “We are continuing to increase the capacity for industrial jobs so that people don’t have to get into their vehicles and drive. But in order for that to continue, we have to make a city that is inviting, that has people places where people can congregate rather than making them jump into a car to go get a jug of milk.”

More than 7,000 people have weighed in with their views. Braun says most have been supportive. But he acknowledges not everyone will be happy, particularly those with outlying properties who might have been able to heavily densify under the old rules.

“Yes, there will be some push back. There are going to be some land owners who are going to be able to build less than what they could before the plan. And some will be able to build more than they could have,” he said.

“We are going to say no to some things that we have historically said yes to, things that are not good enough. But that is what Abbotsford needs now. We all recognize we are a big city and we need to act like a big city.”

Read more:

BCBusiness, Abbotsford wants fewer cars, more parks by Marcie Good, published April 15, 2016

Learn more about Abbotsforward and download/view the draft OCP here